Interesting book that teaches you the power of testing new things by developing “little bets”. Not a new concept for a lean entrepreneur, although this book is focused on the everyday life rather than to entrepreneurship.

The Little Bets Approach

The little bets approach is about using negativity to positive effect. If your plans fall apart, refine them; if you don’t know where best to begin, just begin somewhere. Every decision is a risk: take a chance and see what happens.

Fundamental to the little bets approach is that we:

- Experiment: Learn by doing. Fail quickly to learn fast. Develop experiments and prototypes to gather insights, identify problems, and build up to creative ideas, like Beethoven did in order to discover new musical styles and forms.

- Play: A playful, improvisational, and humorous atmosphere quiets our inhibitions when ideas are incubating or newly hatched, and prevents creative ideas from being snuffed out or prematurely judged.

- Immerse: Take time to get out into the world to gather fresh ideas and insights, in order to understand deeper human motivations and desires, and absorb how things work from the ground up.

- Define: Use insights gathered throughout the process to define specific problems and needs before solving them, just as the Google founders did when they realized that their library search algorithm could address a much larger problem.

- Reorient: Be flexible in pursuit of larger goals and aspirations, making good use of small wins to make necessary pivots and chart the course to completion.

- Iterate: Repeat, refine, and test frequently armed with better insights, information, and assumptions as time goes on, as Chris Rock does to perfect his act.

Two fundamental advantages of the little bets approach are highlighted in the research of Professor Saras Sarasvathy: that it enables us to focus on what we can afford to lose rather than make assumptions about how much we can expect to gain, and that it facilitates the development of means as we progress with an idea.

Sarasvathy points to the value of what she calls the affordable loss principle. Seasoned entrepreneurs, she emphasizes, will tend to determine in advance what they are willing to lose, rather than calculating expected gains. Using a little bets approach facilitates operating according to the affordable loss principle. Bill Hewlett’s small bet on manufacturing one thousand calculators is a great case in point of this kind of thinking, especially when contrasted with HP’s later quest to go after billion dollar markets.

Her work also shows that entrepreneurs tend to be highly aware of the importance of their means, which she defines as:

- Who they are: their values and tastes;

- What they know: their expertise, knowledge, experiences, and skills; and

- Who they know: their networks, friends, and allies. Of course, we should also add their monetary resources.

She highlights that successful entrepreneurs are comfortable being adaptable in pursuit of their larger goals in large part because they are progressively building their means, such as by recruiting people or partners with complementary skills and experiences.

Of course the subject of affordable losses highlights a key issue with the little bets approach—it inevitably involves failure. In almost any attempt to create, failure, and often a good deal of it, is to be expected.

In investigating what facilitates the successful practice of little bets, a certain way of thinking about failure plays an important role. Successful experimental innovators, as we’ll next explore, tend to view failure as both inevitable and instrumental in pursuing their goals.

The Growth Mindset

One of the striking characteristics of those who have learned to practice experimental innovation is that, like Chris Rock, they understand (and come to accept) that failure, in the form of making mistakes or errors, and being imperfect is essential to their success. It’s not that they intentionally try to fail, but rather that they know that they will make important discoveries by being willing to be imperfect, especially at the initial stages of developing their ideas.

By expecting to get things right at the start, we block ourselves psychologically and choke off a host of opportunities to learn. In placing so much emphasis on minimizing errors or the risk of any kind of failure, we shut off chances to identify the insights that drive creative progress. Becoming more comfortable with failure, and coming to view false starts and mistakes as opportunities opens us up creatively.

Dr. Carol Dweck, a professor of social psychology at Stanford University, is one of the leading experts on why some people are more willing (and able) to learn from setbacks. Based until 2004 at Columbia University, Dweck has studied motivation for several decades. Her research has demonstrated that people tend to lean toward one of two general ways of thinking about learning and failure, though everyone exhibits both to some extent. Those favoring a fixed mind-set believe that abilities and intelligence are set in stone, that we have an innate set of talents, which creates an urgency to repeatedly prove those abilities. They perceive failures or setbacks as threatening their sense of worth or their identity.

Conversely, those favoring a growth mind-set believe that intelligence and abilities can be grown through effort, and tend to view failures or setbacks as opportunities for growth. They have a desire to constantly challenge and stretch themselves.

Dozens of studies later, Dweck’s findings suggest that people exhibiting fixed mind-sets tend to gravitate to activities that confirm their abilities, whereas those with growth mind-sets tend to seek activities that expand their abilities.

One of the most important discoveries in Dweck’s research is that a person’s mind-set can be strongly influenced by what he is led to think is more important: ability or effort.

One of the most important insights about the growth mind-set and the productive attitude towards failure that it entails is that it is not about not caring about failure.

“Changing a mind-set is not like surgery,” she says. “You can’t simply remove the fixed mind-set and replace it with a growth mind-set.”

That begins when someone becomes aware of which mindset they lean toward. Simply knowing more about the growth mind-set allows them to react to situations in new ways. So, if a person tends toward a fixed mind-set, they can catch themselves and reframe situations as opportunities to learn rather than viewing them as a potential for failure.

Next Dweck says that people can think about things in their lives that they thought they wouldn’t be good at, but eventually were.

Failing Quickly to Learn Fast

Depending on the form it takes, perfectionism is not necessarily a block to creativity. A growing body of research in psychology has revealed that there are two forms of perfectionism: healthy or unhealthy. Characteristics of what psychologists view as healthy perfectionism include striving for excellence and holding others to similar standards, planning ahead, and strong organizational skills. Healthy perfectionism is internally driven in the sense that it’s motivated by strong personal values for things like quality and excellence. Conversely, unhealthy perfectionism is externally driven. External concerns show up over perceived parental pressures, needing approval, a tendency to ruminate over past performances, or an intense worry about making mistakes.

One of the methods that can be most helpful in achieving this balance, in order to embrace the learning potential of failure, is prototyping. What the creation of low cost, rough prototypes makes possible is failing quickly in order to learn fast. As Pixar director Andrew Stanton, director of Finding Nemo and WALL-E, describes this way of operating, “My strategy has always been: be wrong as fast as we can. Which basically means, we’re gonna screw up, let’s just admit that. Let’s not be afraid of that. But let’s do it as fast as we can so we can get to the answer. You can’t get to adulthood before you go through puberty. I won’t get it right the first time, but I will get it wrong really soon, really quickly.”

Failing quickly to learn fast is also a central operating principle for seasoned entrepreneurs who routinely describe their approach as failing forward. That is, entrepreneurs push ideas into the market as quickly as possible in order to learn from mistakes and failures that will point the way forward.

The use of prototypes, often the rougher the better, also greatly facilitates overcoming the blank-page problem.

At the beginning of any new idea, the possibilities can seem infinite, and that wide-open landscape of opportunity can become a prison of anxiety and self-doubt. This is a key reason why failing fast with lowisk prototypes the way Chris Rock does is so helpful: If we haven’t invested much in developing an idea, emotionally or in terms of time or resources, then we are more likely to be able to focus on what we can learn from that effort than on what we’ve lost in making it. Prototyping is one of the most effective ways to both jump-start our thinking and to guide, inspire, and discipline an experimental approach.

The Importance of Playing and Improvisation

Creating an atmosphere that allows for playfulness and improvisation is one of the most effective ways to inspire the experimentation that leads to the best ideas and insights.

A host of studies indicates that humor creates positive group effects. Many focus on how humor can increase cohesiveness and act as a lubricant to facilitate more efficient communications, like Bob Petersen’s story team. Researchers have developed a general view that effective humor can increase the quantity and quality of group communications. One reason for that is that humor has also been demonstrated to increase trust. In a widely cited study, Professor William Hampes examined the relationship between humor and trust among eighty-nine college undergraduates ranging in age from sixteen to fifty-four and found a significant correlation. The people who scored high on a test that measured sense of humor for social purposes, coping humor, and appreciated humor and humorous people were considered more trustworthy.

In order to produce positive mental effects, however, researchers Eric Romero and Anthony Pescosolido found that humor first must be considered funny to the people involved, not seen as demeaning, derogatory, or put-downs. That finding is consistent with the underlying improvisation rationale for accepting every offer and making your partner look good.

A playful, lighthearted, and humorous environment is especially helpful when ideas are incubating and newly hatched, the phase when they are most vulnerable to being snuffed out or even expressed because of being judged or self-censored. The imagined possibilities become the basis for little bets, just as comedians improvise to develop new material.

Using Constraints

Being able to effectively use constraints takes some doing. With some endeavors, such as architecture, constraints are clearly imposed from the outside. At other times, the possibilities seem limitless, such as the blank-page problem. In situations like these, using self-imposed constraints is a powerful technique. The key is to take a larger project or goal and break it down into smaller problems to be solved, constraining the scope of work to solving a key problem, and then another key problem.

Inherent to agile development is to focus on smallified pieces of work and narrowly defined problems. However, the problems to be solved become better known throughout the process, rather than at the outset. This involves something that creativity research has shown to be a central aide to any creative process: the ability to actively seek out problems, Psychologists Jacob Getzels and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi conducted a seminal study in the 1970s that highlighted the importance of problem finding to creative work.

In a study of thirty-five artists, Getzels and Csikszentmihalyi found that the most creative in their sample were more open to experimentation and to reformulating their ideas for projects than their less creative counterparts. The artists were shown twenty-seven objects, such as cups or trash bins, and were asked to use some of the objects to create a drawing. Problem finders looked at more objects and selected more complicated ones to draw than their counterparts. Finders then explored more possibilities and were willing to switch direction with their drawings when new opportunities presented themselves.

The less creative artists, on the other hand, immediately jumped to drawing objects, leading the researchers to call them “problem solvers.” A panel of independent judges found the problem finders’ work markedly more creative than the problem solvers’ work. In a follow-up study completed eighteen years later, this one expanded

Using Experience

One of the best ways to identify creative insights and develop ideas is to throw out the theory and experience things firsthand. After all, fresh problems, ideas, needs, and desires aren’t obvious; they’re hidden beneath the surface. We can’t even know what questions to ask until we reach beyond what is already known through a true process of discovery: carefully exploring, observing, and listening to uncover what is hidden from the naked eye from the bottom up. In doing so, we must go deep, we must go wide, and we must be focused.

Research evidence suggests a strong link between inquisitiveness and creative productivity. In an extensive six-year study about the way creative executives in business think, for example, Professors Jeffrey Dyer of Brigham Young University and Hal Gregersen of INSEAD, surveyed over three thousand executives and interviewed five hundred people who had either started innovative companies or invented new products.

The authors found several “patterns of action” or “discovery skills” that distinguished the innovators from the noninnovators, which in addition to experimenting, as we’ve seen, included observing, questioning, and networking with people from diverse backgrounds, all of which, Dyer and Gregersen believed, can be developed. As Gregersen wrapped up their findings: “You might summarize all of the skills we’ve noted in one word: ‘

“Creativity is just connecting things,” Jobs told Wired magazine. “When you ask creative people how they did something, they feel a little guilty because they didn’t really do it, they just saw something. It seemed obvious to them after a while. That’s because they were able to connect experiences they’ve had and synthesize new things. And the reason they were able to do that was that they’ve had more experiences or they have thought more about their experiences than other people … Unfortunately, that’s too rare a commodity. A lot of people in our industry haven’t had very diverse experiences. So they don’t have enough dots to connect, and they end up with very linear solutions without a broad perspective on the problem.

The exemplars Dyer and Gregerson highlighted were also voracious questioners, regularly seeking to challenge the status quo by asking “what if?” “why?” and “why not?” The authors wrote that the innovators steer “entirely clear” of what’s called the status quo bias. This research demonstrates that people do not like to change unless there is a compelling reason to do so, such as an attractive incentive. Related research shows that people exhibit strong “loss aversion,” in that they are twice as likely to seek to avoid losses as they are to acquire gains.

The innovators got encouragement to pursue their intrinsic interests from parents, teachers, neighbors, other family members, and the like. As Gregersen shared, “We were struck by the stories they told about being sustained by people who cared about experimentation and exploration.” It’s a powerful finding that emerges time and again. Instead of placing significant value on external measures of achievement, parents of those who become successful creatives tend to emphasize pursuing whatever interests they have. Pixar’s Chief Creative Officer John Lasseter, for example, was interested in cartoons from a young age and was encouraged by his mother to pursue drawing them as a career, starting with art school. The singers and songwriters I interviewed, including John Legend and Kevin Brereton, were heavily influenced during childhood by their families’ extensive music collections.

The Difference Between Lucky and Unlucky People

Indeed, Dyer’s and Gregersen’s finding mirrors a preponderance of evidence that indicates that diversity, be it of perspectives, experiences, or backgrounds, fuels creativity. We see this pattern at the individual, organizational, and societal level.

Let’s turn to the research of Dr. Richard Wiseman, who runs a research unit at the University of Hertfordshire in the United Kingdom and spent ten years studying why some people seem to be lucky, while others seem to be unlucky. To understand whether different behavioral patterns characterized lucky versus unlucky people, Wiseman performed a series of experiments on four hundred people, and summarized his findings in his book The Luck Factor. His study sample included people from all walks of life, ranging in age from eighteen to eighty-four, including secretaries, doctors, computer analysts, factory workers, and businesspeople.

People about whether they perceived themselves to be lucky or unlucky. They found that 50 percent of the respondents considered themselves to be lucky, 36 percent felt they were neither lucky nor unlucky, while fourteen percent said they were consistently unlucky.

Over the next several years, Wiseman sought out differences between these self-described “lucky” and “unlucky” people. He performed in-depth interviews, asked people to complete diaries, and administered a battery of tests, experiments, and questionnaires.

One obvious implication from Wiseman’s research is that lucky people pay more attention to what’s going on around them than unlucky people. It’s more nuanced than that. Here’s where being open to meeting, interacting with, and learning from different types of people comes in. Wiseman found that lucky people tend to be open to opportunities (or insights) that come along spontaneously, whereas unlucky people tend to be creatures of routine, fixated on certain specific outcomes.

In analyzing behavior patterns at social parties, for example, unlucky people tended to talk with the same types of people, people who are like themselves. It’s a common phenomenon. On the other hand, lucky people tended to be curious and open to what can come along from chance interactions. For example, Wiseman found that the lucky people had three times greater open body language in social situations than unlucky people. Lucky people also smiled twice as much as unlucky people, thus drawing other people and chance encounters to them. They didn’t cross their arms or legs and pointed their bodies to other people and increased the likelihood of chance encounters by introducing variety. Chance opportunities favored people who were open to them.

Wiseman believed another type of behavior played an even greater role in success. Wiseman found that lucky people build and maintain what he called a strong network of luck. He wrote:

Lucky people are effective at building secure, and long-lasting, attachments with the people they meet. They are easy to know and most people like them. They tend to be trusting and form close relationships with others. As a result, they often keep in touch with a much larger number of friends and colleagues than unlucky people. And time and again, this network of friends helps promote opportunity in their lives.

This was Wiseman’s core finding: You can create your own luck. “I discovered that being in the right place at the right time is actually all about being in the right state of mind,” he argued. Lucky people increase their odds of chance encounters or experiences by interacting with a large number of people. Extraversion, Wiseman found, pays opportunity and insight rewards. And that makes perfect sense: Chance opportunities are a numbers game. The more people and perspectives in your sphere of reference, the more likely good insights and opportunities will combine.

How Ideas Spread

There’s an important reason that stand-up comedians target small comedy club audiences with their little bets, and it’s backed up by decades of empirical research, including that of MIT Professor Eric von Hippel. Von Hippel showed how these types of cutting-edge users of ideas provide unique insight about what ideas will be valuable to a broader audience. Seeking out a small group of these active users with little bets is an astute way to tap into unique insights and desires.

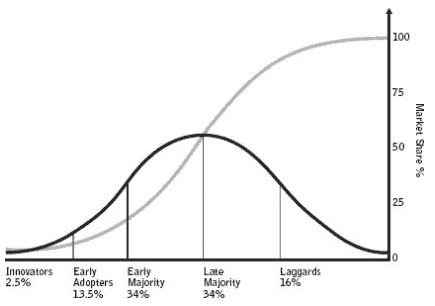

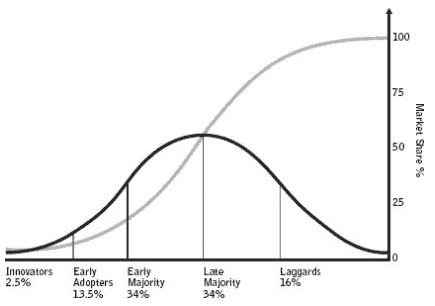

That new ideas travel along a curve of adoption from early to late adopters is now widely accepted. Everett Rogers, the late professor of communications and sociology at Ohio State University, began researching how ideas spread in the 1950s. Rogers coined the term early adopters to describe people who act as trendsetters for new ideas and solutions, people who have insights and preferences that foreshadow those of the masses. He developed his theory by watching how innovations spread along an S-curve of adoption, starting with innovators and early adopters, rising past a tipping point of popularity, before eventually reaching the broad masses, before gradually declining to reach a small number of laggards.

Today, Rogers’s S-curve is ubiquitous and may be applied to the spread of anything, from technologies like iPads to the way new bands become popular to the rise of new words.

Countless other researchers built on Rogers’s body of work, including Eric von Hippel, an economist and professor at the MIT Sloan School of Management, whose research added important insight. For decades, von Hippel has researched how insights from the most active early adopters (what Rogers called the innovators), such as the diehard stand-up audience members, help drive the early stage development of those ideas. Beginning in the 1970s, von Hippel examined where innovations come from (the original source of a later commercialized idea) across a range of industries, from scientific instruments to semiconductors to thermoplastics. In an extensive study on the sources of innovation for major scientific instruments, for instance, von Hippel found that one group, which he called active users or lead users, were responsible for developing over 75 percent of the innovations. A similar pattern ran across an array of other industries. These people not only serve as cutting-edge taste makers, they actively tinker to push and create new ideas on their own.

Since the needs of these active users precede and, according to the research, often anticipate, what the masses will like, they become incredibly valuable as idea development partners. The ideas they help generate can then be tested with broader audiences and commercialized.

Designers call these people extreme users, whose unique needs can foreshadow the needs of other people. The reason why designers find extreme users so valuable is because the average person isn’t actively thinking about solving problems like these. Their needs and desires are less pronounced. As mentioned previously, Steve Jobs will often say, “People don’t know what they want until they’ve seen it.

Small Wins

As we begin to make use of these methods to develop new ideas, strategies, and projects, they combine to facilitate what organizational psychologist Karl Weick refers to as small wins. Weick defines a small win as “a concrete, complete, implemented outcome of moderate importance.” They are small successes that emerge out of our ongoing development process, and it’s important to be watching closely for them. Small wins are like footholds or building blocks amid the inevitable uncertainty of moving forward, or as the case may be, laterally. They serve as what Saras Sarasvathy calls landmarks, and they can either confirm that we’re heading in the right direction or they can act as pivot points, telling us how to change course.

One last, yet important, point about small wins is that often, rather than validating a direction we’ve been pursuing, they will provide a signal to proceed in a different way. In this way, small wins enable a flexibility about how to attain ultimate goals. It is much easier to decide to make a change of approach when we are doing so not because things aren’t working but because something has started to work.

Given the dynamic quality of any discovery process, small wins provide a technique to validate and adapt ideas, to provide clarity amid uncertainty. In some cases, success comes through an accumulation of a series of small wins. In other instances, small wins highlight places to change and pivot, as agile software releases routinely do. The key is to appreciate that we can’t plot a series of small wins in advance, we must use experiments in order for them to emerge.

This brings us back to the fundamental advantages of the little bets approach; it allows us to discover new ideas, strategies, or plans through an emergent process, rather than trying to fully formulate them before we begin, and it facilitates adapting our approach as we go rather than continuing on a course that may lead to failure. Perhaps the crucial insight will come from a prototype, or maybe it’s an observation through immersion or a small win that illuminates a subtle clue. It’s not a linear process from step A to step B to step C. As Richard Wiseman’s research demonstrates, chance favors the open mind, receptivity to what cannot be predicted or imagined based on existing knowledge. With the barriers lowered, the creative mind thrives on continuous experimentation and discovery.

👉 Buy Little Bets on Amazon

🎧 Listen for free on Everand (plus 1+ million other books)