A must read for any tech entrepreneur. It explains the concept of the “Chasm”, the gap between the “early adopters” (the first people that use a product) and the mainstream customers.

Most importantly, it explains the technology adoption life cycle, that is, how people adopt technology. If you’re a tech entrepreneur, don’t skip this book!

| Author | Geoffrey Moore |

|---|---|

| Originally published | 1991 |

| Pages | 227 |

| Genre | Business |

| Goodreads rating | ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️ |

| Buy the book | 🛒 Amazon |

🎧 Listen for free on Everand (plus 1+ million other books)

“Still the bible for entrepreneurial marketing 15 years later.” – Tom Byers, Faculty Director of Stanford Technology Ventures Program

What is the Chasm

The point of greatest peril in the development of a high-tech market lies in making the transition from an early market dominated by a few visionary customers to a mainstream market dominated by a large block of customers who are predominantly pragmatists in orientation. The gap between these two markets, heretofore ignored, is in fact so significant as to warrant being called a chasm, and crossing this chasm must be the primary focus of any long-term high-tech marketing plan. A successful crossing is how high-tech fortunes are made; failure in the attempt is how they are lost.

The Technology Adoption Life Cycle’s Group Profiles

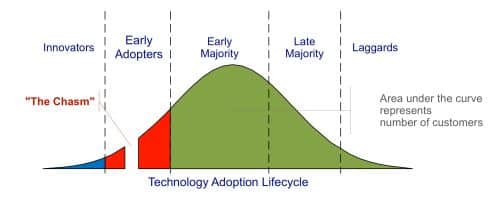

We have a bell curve. The divisions in the curve are roughly equivalent to where standard deviations would fall.

The groups are distinguished from each other by their characteristic response to a discontinuous innovation based on a new technology. Each group represents a unique psychographic profile-a combination of psychology and demographics that makes its marketing responses different from those of the other groups. Understanding each profile and its relationship to its neighbors is a critical component of high-tech marketing lore.

Innovators pursue new technology products aggressively. They sometimes seek them out even before a formal marketing program has been launched. This is because technology is a central interest in their life, regardless of what function it is performing. At root they are intrigued with any fundamental advance and often make a technology purchase simply for the pleasure of exploring the new device’s properties. There are not very many innovators in any given market segment, but winning them over at the outset of a marketing campaign is key nonetheless, because -their endorsement reassures the other players in the marketplace that the product does in fact work.

Early adopters, like innovators, buy into new product concepts very early in their life cycle, but unlike innovators, they are not technologists. Rather they are people who find it easy to imagine, understand, and appreciate the benefits of a new technology, and to relate these potential benefits to their other concerns. Whenever they find a strong match, early adopters are willing to base their buying decisions upon it. Because early adopters do not rely on well-established references in making these buying decisions, preferring instead to rely on their own intuition and vision, they are key to opening up any high-tech market segment.

The early majority share some of the early adopter’s ability to relate to technology, but ultimately they are driven by a strong sense of practicality. They know that many of these newfangled inventions end up as passing fads, so they are content to wait and see how other people are making out before they buy in themselves. They want to see well-established references before investing substantially. Because there are so many people in this segment—roughly one-third of the whole adoption life cycle-winning their business is key to any substantial profits and growth.

The late majority shares all the concerns of the early majority, plus one major additional one: Whereas people in the early majority are comfortable with their ability to handle a technology product, should they finally decide to purchase it, members of the late majority are not. As a result, they wait until something has become an established standard, and even then they want to see lots of support and tend to buy, therefore, from large, well-established companies. Like the early majority, this group comprises about one-third of the total buying population in any given segment. Courting its favor is highly profitable indeed, for while profit margins decrease as the products mature, so do the selling costs, and virtually all the R&D costs have been amortized.

Finally there are the laggards. These people simply don’t want anything to do with new technology, for any of a variety of reasons, some personal and some economic. The only time they ever buy a technological product is when it is buried so deep inside another product—the way, say, that a microprocessor is designed into the braking system of a new car—that they don’t even know it is there. Laggards are generally regarded as not worth pursuing on any other basis.

The Technology Adoption Life Cycle

This profile, is in turn, the very foundation of the High-Tech Marketing Model. That model says that the way to develop a high-tech market is to work the curve left to right, focusing first on the innovators, growing that market, then moving on to the early adopters, growing that market, and so on, to the early majority, late majority, and even to the laggards. In this effort, companies must use each “captured” group as a reference base for going on to market to the next group. Thus, the endorsement of innovators becomes an important tool for developing a credible pitch to the early adopters, that of the early adopters to the early majority, and so on.

This, in essence, is the High-Tech Marketing Model—a vision of a smooth unfolding through all the stages of the Technology Adoption Life Cycle. What is dazzling about this concept, particularly to those who own equity in a hightech venture, is its promise of virtual monopoly over a major new market development. If you can get there first, “catch the curve,” and ride it up through the early majority segment, thereby establishing the de facto standard, you can get rich very quickly and “own” a highly profitable market for a very long time to come.

👉 Buy Crossing the Chasm on Amazon

🎧 Listen for free on Everand (plus 1+ million other books)

The Cracks in the Bell Curve

As you can see, the components of the life cycle are unchanged, but between any two psychographic groups has been introduced a gap. This symbolizes the dissociation between the two groups—that is, the difficulty any group will have in accepting a new product if it is presented in the same way as it was to the group to its immediate left. Each of these gaps represents an opportunity for marketing to lose momentum, to miss the transition to the next segment, thereby never to gain the promised land of profit-margin leadership in the middle of the bell curve.

The First Crack

Two of the gaps in the High-Tech Marketing Model are relatively minor— what one might call “cracks in the bell curve”—yet even here unwary ventures have slipped and fallen. The first is between the innovators and the early adopters. It is a gap that occurs when a hot technology product cannot be readily translated into a major new benefit—something like Esperanto. The enthusiast loves it for its architecture, but nobody else can even figure out how to start using it.

The Other Crack

There is another crack in the bell curve, of approximately equal magnitude, that falls between the early majority and the late majority. By this point in the Technology Adoption Life Cycle, the market is already well developed, and the technology product has been absorbed into the mainstream. The key issue now, transitioning from the early to the late majority, has to do with demands on the end user to be technologically competent.

Simply put, the early majority is willing and able to become technologically competent, where necessary; the late majority, much less so. When a product reaches this point in the market development, it must be made increasingly easier to adopt in order to continue being successful. If this does not occur, the transition to the late majority may well stall or never happen.

The Differences between Early Adopters and the Early Majority

What the early adopter is buying is some kind of change agent. By being the first to implement this change in their industry, the early adopters expect to get a jump on the competition, whether from lower product costs, faster time to market, more complete customer service, or some other comparable business advantage. They expect a radical discontinuity between the old ways and the new, and they are prepared to champion this cause against entrenched resistance. Being the first, they also are prepared to bear with the inevitable bugs and glitches that accompany any innovation just coming to market.

By contrast, the early majority want to buy a productivity improvement for existing operations. They are looking to minimize the discontinuity with the old ways. They want evolution, not revolution. They want technology to enhance, not overthrow, the established ways of doing business. And above all, they do not want to debug somebody else’s product. By the time they adopt it, they want it to work properly and to integrate appropriately with their existing technology base.

This contrast just scratches the surface relative to the differences and incompatibilities among early adopters and the early majority. Let me just make two key points for now: Because of these incompatibilities, early adopters do not make good references for the early majority. And because of the early majority’s concern not to disrupt their organizations, good references are critical to their buying decisions. So what we have here is a catch-22. The only suitable reference for an early majority customer, it turns out, is another member of the early majority, but no upstanding member of the early majority will buy without first having consulted with several suitable references.

Marketing and High-Tech Market Definition

Marketing’s purpose is to develop and shape something that is real, and not, as people sometimes want to believe, to create illusions. In other words, we are dealing with a discipline more akin to gardening or sculpting than, say, to spray painting or hypnotism.

Of course, talking this way about marketing merely throws the burden of definition onto market, which we will define, for the purposes of high tech, as:

- a set of actual or potential customers

- for a given set of products or services

- who have a common set of needs or wants, and

- who reference each other when making a buying decision.

People intuitively understand every part of this definition except the last. Unfortunately, getting the last part—the notion that part of what defines a high-tech market is the tendency of its members to reference each other when making buying decisions—is absolutely key to successful high-tech marketing. So let’s make this as clear as possible.

If two people buy the same product for the same reason but have no way they could reference each other, they are not part of the same market.

Market Segments

Market, when it is defined in this sense, ceases to be a single, isolable object of action—it no longer refers to any single entity that can be acted on—and cannot, therefore, be the focus of marketing.

The way around this problem for many marketing professionals is to break up “the market” into isolable “market segments.” Market segments, in this vocabulary, meet our definition of markets, including the selfeferencing aspect. When marketing consultants sell market segmentation studies, all they are actually doing is breaking out the natural market boundaries within an aggregate of current and potential sales.

Early Markets: Innovators & Visionaries

The initial customer set for a new technology product is made up primarily of innovators and early adopters. In the high-tech industry, the innovators are better known as technology enthusiasts or just techies, whereas the early adopters are the visionaries. It is the latter group, the visionaries, who dominate the buying decisions in this market, but it is the technology enthusiasts who are first to realize the potential in the new product. High-tech marketing, therefore, begins with the techies.

The Innovator’s Profile

Classically, the first people to adopt any new technology are those who appreciate the technology for its own sake.

They are the ones who first appreciate the architecture of your product and why it therefore has a competitive advantage over the current crop of products established in the marketplace. They are the ones who will spend hours trying to get products to work that, in all conscience, never should have been shipped in the first place. They will forgive ghastly documentation, horrendously slow performance, ludicrous omissions in functionality, and bizarrely obtuse methods of invoking some needed function—all in the name of moving technology forward. They make great critics because they truly care.

In business, technology enthusiasts are the gatekeepers for any new technology. They are the ones who have the interest to learn about it and the ones everyone else deems competent to do the early evaluation. As such, they are the first key to any high-tech marketing effort.

As a buying population, or as key influences in corporate buying decisions, technology enthusiasts pose fewer requirements than any other group in the adoption profile—but you must not ignore the issues that are important to them. First, and most crucially, they want the truth, and without any tricks. Second, wherever possible, whenever they have a technical problem, they want access to the most technically knowledgeable person to answer it. Often this may not be sound from a management point of view, and you will have to deny or restrict such access, but you should never forget that it is wanted.

Third, they want to be first to get the new stuff. By working with them under nondisclosure-a commitment to which they typically adhere scrupulously— you can get great feedback early in the design cycle and begin building a supporter who will influence buyers not only in his own company but elsewhere in the marketplace as well. Finally, they want everything cheap. This is sometimes a matter of budgets, but it is more fundamentally a problem of perception—they think all technology should be free or available at cost, and they have no use for “added-value” arguments. The key consequence here is, if it is their money, you have to make it available cheap, and if it is not, you have to make sure price is not their concern.

In large companies, technology enthusiasts can most often be found in the advanced technology group, or some such congregation, chartered with keeping the company abreast of the latest developments in high tech. There they are empowered to buy one of almost anything, simply to explore its properties and examine its usefulness to the corporation. In smaller companies, which do not have such budgetary luxuries, the technology enthusiast may well be the “designated techie” in the MIS group or a member of a product design team who either will design your product in or supply it to the rest of the team as a technology aid or tool.

To reach technology enthusiasts, you need to place your message in one of their various haunts—on the Web, of course. Direct response advertising works well with this group, as they are the segment most likely to send for literature, or a free demo, or whatever you offer. Finally, don’t waste your time with a lot of fancy image advertising—they read all that as just marketing hype. Direct e-mail will reach them—and provided it is factual and new information, they read cover to cover.

In sum, technology enthusiasts are easy to do business with, provided you (1) have the latest and greatest technology, and (2) don’t need to make much money. For any innovation, there will always be a small class of these enthusiasts who will want to try it out just to see if it works. For the most part, these people are not powerful enough to dictate the buying decisions of others, nor do they represent a significant market in themselves. What they represent instead is a beachhead, a source of initial product or service references, and a test bed for introducing modifications to the product or service until it is thoroughly “debugged.”

👉 Buy Crossing the Chasm on Amazon

🎧 Listen for free on Everand (plus 1+ million other books)

The Visionarie’s (Early Adopters) Profile

Visionaries are that rare breed of people who have the insight to match an emerging technology to a strategic opportunity, the temperament to translate that insight into a high-visibility, highisk project, and the charisma to get the rest of their organization to buy into that project. They are the early adopters of high-tech products. Often working with budgets in the multiple millions of dollars, they represent a hidden source of venture capital that funds hightechnology business.

As a class, visionaries tend to be recent entrants to the executive ranks, highly motivated, and driven by a “dream.” The core of the dream is a business goal, not a technology goal, and it involves taking a quantum leap forward in how business is conducted in their industry or by their customers. It also involves a high degree of personal recognition and reward. Understand their dream, and you will understand how to market to them.

Visionaries are not looking for an improvement; they are looking for a fundamental breakthrough. Technology is important only insomuch as it promises to deliver on this dream. If the dream is cell phone usage anywhere, then the system will involve a matrix of Low-Earth- Orbit satellites such as Iridium or Teledesic. If it is one-on-one marketing, then the technology will include data mining of transaction-processing databases such as that provided by BM’s Intelligent Miner. If it is an inventoryless supply chain then it will include advanced planning, forecasting, and replenishment algorithms combined to intercompany systems integration as companies like Manugistics and I2 bring to market.

Visionaries drive the high-tech industry because they see the potential for an “order-of-magnitude” return on investment and willingly take high risks to pursue that goal. They will work with vendors who have little or no funding, with products that start life as little more than a diagram on a whiteboard, and with technology gurus who bear a disconcerting resemblance to Rasputin. They know they are going outside the mainstream, and they accept that as part of the price you pay when trying to leapfrog the competition.

Because they see such vast potential for the technology they have in mind, they are the least price-sensitive of any segment of the technology adoption profile. They typically have budgets that let them allocate generous amounts toward the implementation of a strategic initiative. This means they can usually provide up-front money to seed additional development that supports their project—hence their importance as a source of high-tech development capital.

Finally, beyond fueling the industry with dollars, visionaries are also effective at alerting the business community to pertinent technology advances. Outgoing and ambitious as a group, they are usually more than willing to serve as highly visible references, thereby drawing the attention of the business press and additional customers to small fledgling enterprises.

As a buying group, visionaries are easy to sell but very hard to please. This is because they are buying a dream—which, to some degree, will always be a dream. The “incarnation” of this dream will require the melding of numerous technologies, many of which will be immature or even nonexistent at the beginning of the project. The odds against everything falling into place without a hitch are astronomical. Nonetheless, both the buyer and the seller can build successfully on two key principles.

First, visionaries like a project orientation. They want to start out with a pilot project, which makes sense because they are “going where no man has gone before” and you are going with them. This is followed by more project work, conducted in phases, with milestones, and the like. The visionaries’ idea is to be able to stay very close to the development train to make sure it is going in the right direction and to be able to get off if they discover it is not going where they thought.

The winning strategy is built around the entrepreneur being able to “productize” the deliverables from each phase of the visionary project. That is, whereas for the visionary the deliverables of phase one are only of marginal interest—proof of concept with some productivity improvement gained, but not “the vision”— these same deliverables, repackaged, can be a whole product to someone with less ambitious goals. For example, a company might be developing a comprehensive object-oriented software toolkit, capable of building systems that could model the entire workings of a manufacturing plant, thereby creating an order-of-magnitude improvement in scheduling and processing efficiency. The first deliverable of the toolkit might be a model of just one milling machine’s operations and its environment. The visionary looks at that model as a milestone. But the vendor of that milling machine might look at the same model as a very desirable product alterations and want to license it with only modest alterations. It is important, therefore, in creating the phases of the visionary’s project to build in milestones that lend themselves to this sort of product spin-off.

The other key quality of visionaries is that they are in a hurry. They see the future in terms of windows of opportunity, and they see those windows closing. As a result, they tend to exert deadline pressures—the carrot of a big payment or the stick of a penalty clause—to drive the project faster. This plays into the classic weaknesses of entrepreneurs—lust after the big score and overconfidence in their ability to execute within any given time frame.

Here again, account management and executive restraint are crucial. The goal should be to package each of the phases such that each phase:

- is accomplishable by mere mortals working in earth time

- provides the vendor with a marketable product

- provides the customer with a concrete return on investment that can be celebrated as a major step forward.

The last point is crucial. Getting closure with visionaries is next to impossible. Expectations derived from dreams simply cannot be met. This is not to devalue the dream, for without it there would be no directing force to drive progress of any sort. What is important is to celebrate continually the tangible and partial as both useful things in their own right and as heralds of the new order to come.

The most important principle stemming from all this is the emphasis on management of expectations. Because controlling expectations is so crucial, the only practical way to do business with visionaries is through a small, toplevel direct sales force. At the front end of the sales cycle, you need such a group to understand the visionaries’ goals and give them confidence that your company can step up to them. In the middle of the sales cycle, you need to be extremely flexible about commitments as you begin to adapt to the visionaries’ agenda. At the end, you need to be very careful in negotiations, keeping the spark of the vision alive without committing to tasks that are unachievable within the time frame allotted. All this implies a mature and sophisticated representative working on your behalf.

In terms of prospecting for visionaries, they are not likely to have a particular job title, except that, to be truly useful, they must have achieved at least a vice presidential level in order to have the clout to fund their visions In fact, in terms of communications, typically you don’t find them, they find you. The way they find you, interestingly enough, is by maintaining relationships with technology enthusiasts. That is one of the reasons why it is so important to capture the technology enthusiast segment.

In sum, visionaries represent an opportunity early in a product’s life cycle to generate a burst of revenue and gain exceptional visibility. The opportunity comes with a price tag—a highly demanding customer who will seek to influence your company’s priorities directly and a highisk project that could end in disappointment for all. But without this boost many high-tech products cannot make it to market, unable to gain the visibility they need within their window of opportunity, or unable to sustain their financial obligations while waiting for their marketplace to develop more slowly. Visionaries are the ones who give high-tech companies their first big break. It is hard to plan for them in marketing programs, but it is even harder to plan without them.

Mainstream Markets: Pragmatists and Convervatives

Mainstream markets in high tech look a lot like mainstream markets in any other industry, particularly those that sell business to business. They are dominated by the early majority, who in high tech are best understood as pragmatists, who, in turn, tend to be accepted as leaders by the late majority, best thought of as conservatives, and rejected as leaders by the laggards, or skeptics.

The Pragmatist’s (Early Majority) Profile

You can succeed with the visionaries, and you can thereby get a reputation for being a high flyer with a hot product, but that is not ultimately where the dollars are. Instead, those funds are in the hands of more prudent souls, who do not want to be pioneers (“Pioneers are people with arrows in their backs”), who never volunteer to be an early test site (“Let somebody else debug your product”), and who have learned the hard way that the “leading edge” of technology is all too often the “bleeding edge.”

Who are the pragmatists? Actually, important as they are, they are hard to characterize because they do not have the visionary’s penchant for drawing attention to themselves.

In the realm of high tech, pragmatist CEOs are not common, and those there are, true to their type, tend to keep a relatively low profile.

Of course, to market successfully to pragmatists, one does not have to be one—just understand their values and work to serve them. To look more closely into these values, if the goal of visionaries is to take a quantum leap forward, the goal of pragmatists is to make a percentage improvement—incremental, measurable, predictable progress. If they are installing a new product, they want to know how other people have fared with it. The word risk is a negative word in their vocabulary—it does not connote opportunity or excitement but rather the chance to waste money and time. They will undertake risks when required, but they first will put in place safety nets and manage the risks very closely.

If pragmatists are hard to win over, they are loyal once won, often enforcing a company standard that requires the purchase of your product, and only your product, for a given requirement. This focus on standardization is, well, pragmatic, in that it simplifies internal service demands. But the secondary effects of this standardization—increasing sales volumes and lowering the cost of sales—is dramatic. Hence the importance of pragmatists as a market segment.

When pragmatists buy, they care about the company they are buying from, the quality of the product they are buying, the infrastructure of supporting products and system interfaces, and the reliability of the service they are going to get. In other words, they are planning on living with this decision personally for a long time to come. (By contrast, the visionaries are more likely to be planning on implementing the great new order and then using that as a springboard to their next great career step upward.) Because pragmatists are in it for the long haul, and because they control the bulk of the dollars in the marketplace, the rewards for building relationships of trust with them are very much worth the effort.

Pragmatists tend to be “vertically” oriented, meaning that they communicate more with others like themselves within their own industry than do technology enthusiasts and early adopters, who are more likely to communicate “horizontally” across industry boundaries in search of kindred spirits. This means it is very tough to break into a new industry selling to pragmatists. References and relationships are very important to these people, and there is a kind of catch-22 operating: Pragmatists won’t buy from you until you are established, yet you can’t get established until they buy from you. Obviously, this works to the disadvantage of start-ups and, conversely, to the great advantage of companies with established track records. On the other hand, once a start-up has earned its spurs with the pragmatist buyers within a given vertical market, they tend to be very loyal to it, and even go out of their way to help it succeed. When this happens, the cost of sales goes way down, and the leverage on incremental R&D to support any given customer goes way up. That’s one of the reasons pragmatists make such a great market.

There is no one distribution channel preferred by pragmatists, but they do want to keep the sum total of their distribution relationships to a minimum. This allows them to maximize their buying leverage and maintain a few clear points of control, should anything go wrong. In some cases this prejudice can be overcome if the pragmatist buyer knows a particular salesperson from a previous relationship. As a rule, however, the path into the pragmatist community is smoother if a smaller entrepreneurial vendor can develop an alliance with one of the already accepted vendors or if it can establish a value-addedreseller (VAR) sales base. VARs, if they truly specialize in the pragmatist’s particular industry, and if they have a reputation for delivering quality work on time and within budget, represent an extremely attractive type of solution to a pragmatist. They can provide a “turn-key” answer to a problem, without impacting internal resources already overloaded with the burdens of ongoing system maintenance. What the pragmatist likes best about VARs is that they represent a single point of control, a single company to call if anything goes wrong.

One final characteristic of pragmatist buyers is that they like to see competition— in part to get costs down, in part to have the security of more than one alternative to fall back on, should anything go wrong, and in part to assure themselves they are buying from a proven market leader. This last point is crucial: Pragmatists want to buy from proven market leaders because they know that third parties will design supporting products around a market-leading product. That is, market-leading products create an aftermarket that other vendors service. This radically reduces pragmatist customers’ burden of support. By contrast, if they mistakenly choose a product that does not become the market leader, but rather one of the alsoans, then this highly valued aftermarket support does not develop, and they will be stuck making all the enhancements by themselves. Market leadership is crucial, therefore, to winning pragmatist customers.

Pragmatists are reasonably price-sensitive. They are willing to pay a modest premium for top quality or special services, but in the absence of any special differentiation, they want the best deal. That’s because, having typically made a career commitment to their job and/or their company, they get measured year in and year out on what their operation has spent versus what it has returned to the corporation.

Overall, to market to pragmatists, you must be patient. You need to be conversant with the issues that dominate their particular business. You need to show up at the industry-specific conferences and trade shows they attend. You need to be mentioned in articles that run in the magazines they read. You need to be installed in other companies in their industry. You need to have developed applications for your product that are specific to the industry. You need to have partnerships and alliances with the other vendors who serve their industry. You need to have earned a reputation for quality and service. In short, you need to make yourself over into the obvious supplier of choice.

The Conservative’s (Late Majority) Profile

The mathematics of the Technology Adoption Life Cycle model says that for every pragmatist there is a conservative. Put another way, conservatives represent approximately one-third of the total available customers within any given Technology Adoption Life Cycle. As a marketable segment, however, they are rarely developed as profitably as they could be, largely because high-tech companies are not, as a rule, in sympathy with them. Conservatives, in essence, are against discontinuous innovations. They believe far more in tradition than in progress. And when they find something that works for them, they like to stick with it.

In this sense, conservatives have more in common with early adopters than one might think. Both can be stubborn in their resistance to the call to conform that unites the pragmatist herd. To be sure, in many cases both do succumb to the new paradigm, long after it was really new, just to stay on par with the rest of the world. But just because conservatives use such products, they don’t necessarily have to like them.

The truth is, conservatives often fear high tech a little bit. Therefore, they tend to invest only at the end of a technology life cycle, when products are extremely mature, market-share competition is driving low prices, and the products themselves can be treated as commodities. Often their real goal in buying high-tech products is simply not to get stung. Unfortunately, because they are working the low-margin end of the market, where there is little motive for the seller to build a high-integrity relationship with the buyer, they often do get stung. This only reinforces their disillusion with high tech and resets the buying cycle at an even more cynical level.

If high-tech businesses are going to be successful over the long term, they must learn to break this vicious circle and establish a reasonable basis for conservatives to want to do business with them. They must understand that conservatives do not have high aspirations about their high-tech investments and hence will not support high price margins. Nonetheless, through sheer volume, they can offer great rewards to the companies that serve them appropriately.

Conservatives like to buy preassembled packages, with everything bundled, at a heavily discounted price. The last thing they want to hear is that the software they just bought doesn’t support the printer they have installed. They want high-tech products to be like refrigerators—you open the door, the light comes on automatically, your food stays cold, and you don’t have to think about it. The products they understand best are those dedicated to a single function—word processors, calculators, copiers, and fax machines. The notion that a single computer could do all four of these functions does not excite them—instead, it is something they find vaguely nauseating.

The conservative marketplace provides a great opportunity, in this regard, to take low-cost, trailing-edge technology components and repackage them into single-function systems for specific business needs. The quality of the package should be quite high because there is nothing in it that has not already been thoroughly debugged. The price should be quite low because all the R&D has long since been amortized, and every bit of the manufacturing learning curve has been taken advantage of. It is, in short, not just a pure marketing ploy but a true solution for a new class of customer.

There are two keys to success here. The first is to have thoroughly thought through the “whole solution” to a particular target end user market’s needs, and to have provided for every element of that solution within the package. This is critical because there is no profit margin to support an afterpurchase support system. The other key is to have lined up a low-overhead distribution channel that can get this package to the target market effectively.

Despite such successes, however, one has the feeling that the conservative market is perceived more as a burden than an opportunity. High-tech business success within it will require a new kind of marketing imagination linked to a less venturesome financial model. The dollars are there for the making if we can meet new challenges that are as yet only partially familiar. However, as the cost of R&D radically escalates, companies are going to have to amortize that cost across bigger and bigger markets, and this must inevitably lead to the long ignored “back half ” of the technology adoption curve.

How to Make the Transition from Pragamtists to Conservatives

The key to making a smooth transition from the pragmatist to the conservative market segments is to maintain a strong relationship with the former, always giving them an open door to go to the new paradigm, while still keeping the latter happy by adding value to the old infrastructure. It is a balancing act to say the least, but properly managed the earnings potential in loyal mature market segments is very high indeed.

In this regard, if we now look back over the first four profiles in the Technology Adoption Life Cycle, we see an interesting trend. The importance of the product itself, its unique functionality, when compared to the importance of the ancillary services to the customer, is at its highest with the technology enthusiast, and, at its lowest with the conservative. This is no surprise, since one’s level of involvement and competence with a high-tech product are a prime indicator of when one will enter the Technology Adoption Life Cycle. The key lesson is that the longer your product is in the market, the more mature it becomes, and the more important the service element is to the customer. Conservatives, in particular, are extremely service oriented.

Now, it would be a much simpler world if conservatives were willing to pay for all this service they require. But they are not. So the corollary lesson is, we must use our experience with the pragmatist customer segment to identify all the issues that require service and then design solutions to these problems directly into the product. This must be the focus of mature market R&D— not the extension of functionality, not the massive rewrite from the ground up, but the gradual incorporation into the product of all the little aids that people develop, often on their own, to help them cope with its limitations. This is service indeed, for the best service, both from the point of view of convenience to the customer and low cost to the vendor, is no service at all.

The Laggard’s (Skeptics) Profile

Skeptics—the group that makes up the last one-sixth of the Technology Adoption Life Cycle—do not participate in the high-tech marketplace, except to block purchases. Thus, the primary function of high-tech marketing in relation to skeptics is to neutralize their influence. In a sense, this is a pity because skeptics can teach us a lot about what we are doing wrong—hence this postscript.

One of the favorite arguments of skeptics is that the billions of dollars invested in office automation have not improved the productivity of the office place one iota.

What skeptics are struggling to point out is that new systems, for the most part, don’t deliver on the promises that were made at the time of their purchase. This is not to say they do not end up delivering value, but rather that the value they actually deliver is not often anticipated at the time of purchase. If this is true— and to some degree I believe it is—it means that committin to a new system is a much greater act of faith than normally imagined. It means that the primary value in the act derives more from such notions as supporting a bias toward action than from any quantifiable packet of cost-justified benefits. The idea that the value of the system will be discovered rather than known at the time of installation implies, in turn, that product flexibility and adaptability, as well as ongoing account service, should be critical components of any buyer’s evaluation checklist.

Ultimately the service that skeptics provide to high-tech marketers is to point continually to the discrepancies between the sales claims and the delivered product. These discrepancies, in turn, create opportunities for the customer to fail, and such failures, through word of mouth, will ultimately come back to haunt us as lost market share. Steamrolling over the skeptics, in other words, may be a great sales tactic, but it is a poor marketing one.

How to Get into the Mainstream

To enter the mainstream market is an act of aggression. The companies who have already established relationships with your target customer will resent your intrusion and do everything they can to shut you out. The customers themselves will be suspicious of you as a new and untried player in their marketplace. No one wants your presence. You are an invader.

This is not a time to focus on being nice. As we have already said, the perils of the chasm make this a life-or-death situation for you. You must win entry to the mainstream, despite whatever resistance is posed. So, if we are going to be warlike, we might as well be so explicitly. For guidance, we are going to look back to an event in the first half of this century, the Allied invasion of Normandy on D Day, June 6, 1944. To be sure, there are more current examples of military success, but this particular analogy relates to our specific concerns very well.

The comparison is straightforward enough. Our long-term goal is to enter and take control of a mainstream market (Eisenhower’s Europe) that is currently dominated by an entrenched competitor (the Axis). For our product to wrest the mainstream market from this competitor, we must assemble an invasion force comprising other products and companies (the Allies). By way of entry into this market, our immediate goal is to transition from an early market base (England) to a strategic target market segment in the mainstream (the beaches at Normandy). Separating us from our goal is the chasm (the English Channel). We are going to cross that chasm as fast as we can with an invasion force focused directly and exclusively on the point of attack (D Day). Once we force the competitor out of our targeted niche markets (secure the beachhead), then we will move out to take over additional market segments (districts of France) on the way toward overall market domination (the liberation of Europe).

That’s it. That’s the strategy. Replicate D Day, and win entry to the mainstream. Cross the chasm by targeting a very specific niche market where you can dominate from the outset, force your competitors out of that market niche, and then use it as a base for broader operations. Concentrate an overwhelmingly superior force on a highly focused target. It worked in 1944 for the Allies, and it has worked since for any number of high-tech companies.

Segmenting to Win

Consider the following. One of the keys in breaking into a new market is to establish a strong word-of-mouth reputation among buyers. Now, for word of mouth to develop in any particular marketplace, there must be a critical mass of informed individuals who meet from time to time and, in exchanging views, reinforce the product’s or the company’s positioning. That’s how word of mouth spreads.

Seeding this communications process is expensive, particularly once you leave the early market, which in general can be reached through the technical press and related media, and make the transition into the mainstream market. Pragmatist buyers, as we have already noted, communicate along industry lines or through professional associations. Chemists talk to other chemists, lawyers to other lawyers, insurance executives to other insurance executives, and so one. Winning over one or two customers in each of 5 or 10 different segments—the consequence of taking a sales-driven approach—will create no word-of-mouth effect. Your customers may try to start a conversation about you, but there will be no one there to reinforce it. By contrast, winning four or five customers in one segment will create the desired effect. Thus, the segment- targeting company can expect word-of-mouth leverage early in its crossing- the-chasm marketing effort, whereas the sales-driven company will get it much later, if at all. This lack of word of mouth, in turn, makes selling the product that much harder, thereby adding to the cost and the unpredictability of sales.

Now, by definition, when you are crossing the chasm, you are not a market leader. The question is, How can you accelerate achieving that state? This is a matter of simple mathematics. To be the leader in any given market, you need the largest market share—typically over 50 percent at the beginning of a market, although it may end up to be as little as 30 to 35 percent later on. So, take the sales you expect to generate over any given time period—say the next two years—double that number, and that’s the size of market you can expect to dominate. Actually, to be precise, that is the maximum size of market, because the calculation assumes that all your sales came from a single market segment. So, if we want market leadership early on—and we do, since we know pragmatists tend to buy from market leaders, and our number one marketing goal is to achieve a pragmatist installed base that can be referenced— the only right strategy is to take a “big fish, small pond” approach.

Segment. Segment. Segment. One of the other benefits of this approach is that it leads directly to you “owning” a market. That is, you get installed by the pragmatists as the leader, and from then on, they conspire to help keep you there. mainstream customers like to be “owned”—it simplifies their buying decisions, improves the quality and lowers the cost of whole product ownership, and provides security that the vendor is here to stay. They demand attention, but they are on your side. As a result, an owned market can take on some of the characteristics of an annuity—a building block in good times, and a place of refuge in bad—with far more predictable revenues and far lower cost of sales than can otherwise be achieved.

For all these reasons—for whole product leverage, for word-of-mouth effectiveness, and for perceived market leadership—it is critical that, when crossing the chasm, you focus exclusively on achieving a dominant position in one or two narrowly bounded market segments. If you do not commit fully to this goal, the odds are overwhelmingly against your ever arriving in the mainstream market.

How to Move Beyond the Initial Target

The key to moving beyond one’s initial target niche is to select strategic target market segments to begin with. That is, target a segment that, by virtue of its other connections, creates an entry point into a larger segment. For example, when the Macintosh crossed the chasm, the target niche was the graphics arts department in Fortune 500 companies. This was not a particularly large target market, but it was one that was responsible for a broken, mission-critical process—providing presentations for executives and marketing professionals. The fact that the segment was relatively small turned out to be good news because Apple was able to dominate it quickly and establish its proprietary system as a legitimate standard within the corporation (against the wishes of the MIS department which wanted everyone on an IBM PC). More importantly, however, having dominated this niche, the company was then able to leverage its win into adjacent departments within the corporation—first marketing, then sales. The marketing people found that if they made their own presentations they could update them on the way to the trade shows, and the salespeople found that with a Mac they didn’t have to rely on the marketing people. At the same time, this beachhead in graphics arts also extended out into external markets that interfaced with the graphics arts people—creative agencies, advertising agencies, and eventually, publishers. All used the Macintosh to exchange a variety of graphic materials, and the result was a complete ecosystem standardized on the “non-standard” platform.

Crossing the Chasm

The answer when crossing the chasm is clear: Make a total commitment to the niche, and then do your best to meet everyone else’s needs with whatever resources you have left over. In the case of Clarify it made a total commitment to the network hardware companies, winning in short order other key market leaders like Wellfleet, 3Com, and Synoptics, which then gave it the credibility to win additional lesser known companies. These customers, first and foremost, wanted case routing that interfaced with their development organizations’ bug reporting applications to ensure that bugs were trapped, tagged, and tracked through to elimination. They also wanted knowledge bases that could capture for reuse highly complex technical knowledge. These were two of the key needs that Clarify prioritized above all their other requests to ensure they helped these customers be successful across the niche.

And so it goes. Winning the beachhead, knocking over the head pin, creates a dynamic of follow-on adoption, opening up new market opportunities, in part from leveraging a solution from one niche to another, in part from wordof- mouth interaction between customers in the adjacent niches. It worked for Clarify, just as it worked for the company to which we will turn next.

Piciking a Chasm-Crossing Target

The answer is that when you are picking a chasm-crossing target it is not about the number of people involved, it is about the amount of pain they are causing. In the case of the pharmaeutical industry’s regulatory affairs function, the pain was excruciating. This is the group that has to get the New Drug Approval applications submitted to the 100 or so different regulatory bodies around the world. The process does not start until patents are awarded. The patents have a 17 year life, and a successful patented drug generates on average about $400 million per year. Once the drug goes off patent, however, its economic returns plummet. Every day spent in the application process is a day of patent-life wasted. Pharmaceutical companies were taking up to one year to get their first application filed—not a year to get it approved, a year to get it submitted!

That was because applications range from 250 to 500 thousand pages in length, and come from a myriad of sources— clinical trial studies, correspondence, manufacturing databases, the Patent Office, research lab notebooks, and the like. All this material has to be frozen in time as a master copy, against which all subsequent changes in information are posted and tracked. It is a nightmare of a problem, and it was costing the drug companies big bucks.

By tackling this problem, Documentum ensured itself of a strongly committed customer. The commitment did not come from the IT organization, which pragmatically was content to work with its established vendors, making continuous improvements to the existing document management infrastructure. Instead, it came from the top brass who, seeing in Documentum a chance to reengineer the entire process to a very different new end, overruled the in-house folks and demanded that they support the new paradigm. This is a standard pattern in crossing the chasm. It is normally the departmental function who leads (they have the problem), the executive function who prioritizes (the problem is causing enterprise-wide grief), and the technical function that follows (they have to make the new stuff work while still maintaining all the old stuff).

And that is pretty much the chain of events that had taken Documentum to over $100 million in revenues. It is niche marketing at its most leveraged. There are two keys to this entire sequence. The first is knocking over the head pin, taking the beachhead, crossing the chasm. The size of the first pin is not the issue, but the economic value of the problem it fixes is. The more serious the problem, the faster the target niche will pull you out of the chasm. Once out, your opportunities to expand into other niches are immensely increased because now, having one set of customers solidly behind you, you are much less risky to back as a new vendor.

The second key is to have lined up other market segments into which you can leverage your initial niche solution. This allows you to reinterpret the financial gain in crossing the chasm. It is not about the money you make from the first niche: It is the sum of that money plus the gains from all subsequent niches. It is a bowling alley estimate, not just a head pin estimate, that should drive the calculation of gain. This is a particularly important point for entrepreneurs working inside large corporations who are having to compete for funding against larger, more established market opportunities. If the executive council cannot see the extended market, if they only see the first niche, they won’t fund. Conversely, if you go the other way, and show them only an aggregated mass market, the end result of the market going horizontal and into hypergrowth, they will fund, but then they will fire you as you fail to generate these spectacular numbers quickly. The bowling pin model allows you both to focus on the immediate market, keeping the burn rate down and the market development effort targeted, while still keeping in view the larger win.

Targeting the Point of Attack

Informed Intuition

The only proper response to the Chasm is to acknowledge the lack of data as a condition of the process. To be sure, you can fight back against this ignorance by gathering highly focused data yourself. But you cannot expect to transform a low-data situation into a high-data situation quickly. And given that you must act quickly, you need to approach the decision from a different vantage point. You need to understand that informed intuition, rather than analytical reason, is the most trustworthy decision-making tool to use.

The key is to understand how intuition—specifically, informed intuition— actually works. Unlike numerical analysis, it does not rely on processing a statistically significant sample of data in order to achieve a given level of confidence. Rather, it involves conclusions based on isolating a few high-quality images—really, data fragments—that it takes to be archetypes of a broader and more complex reality. These images simply stand out from the swarm of mental material that rattles around in our heads. They are the ones that are memorable. So the first rule of working with an image is: If you can’t remember it, don’t try, because it’s not worth it. Or, to put this in the positive form: Only work with memorable images.

Let us call these images characterizations. As such, they represent characteristic market behaviors.

Now, visionaries, pragmatists, and conservatives represent a set of images analogous to teenybopper, yuppie, and so on—albeit at a higher level of abstraction. For each of these labels also represents characteristic market behaviors— specifically, in relation to adopting a discontinuous innovation— from which we can predict the success or failure of marketing tactics. The problem is, they are too abstract. They need to become more concrete, more target- market specific. That is the function of target-customer characterization.

Target-Customer Charecterization

First, please note that we are not focusing here on target-market characterization. The place most crossing-the-chasm marketing segmentation efforts get into trouble is at the beginning, when they focus on a target market or target segment instead of on a target customer.

Markets are impersonal, abstract things: the personal computer market, the one-megabit RAM market, the office automation market, and so on. Neither the names nor the descriptions of markets evoke any memorable images—they do not elicit the cooperation of one’s intuitive faculties. We need to work with something that gives more clues about how to proceed. We need something that feels a lot more like real people. However, since we do not have real live customers as yet, we are just going to have to make them up. Then, once we have their images in mind, we can let’ them guide us to developing a truly responsive approach to their needs.

Target-customer characterization is a formal process for making up these images, getting them out of individual heads and in front of a marketing decision-making group. The idea is to create as many characterizations as possible, one for each different type of customer and application for the product. (It turns out that, as these start to accumulate, they begin to resemble one another so that, somewhere between 20 and 50, you realize you are just repeating the same formulas with minor tweaks, and that in fact you have outlined 8 to 10 distinct alternatives.) Once we have built a basic library of possible targetcustomer profiles, we can then apply technique to reduce these “data” into a prioritized list of desirable target market segment opportunities. The quotation marks around data are key, of course, because we are still operating in a low-data situation. We just have a better set of material to work with.

Calculating the Customer’s Market Size

To become a going concern, a persistent entity in the market, you need a customer market that will commit to you as its de facto standard for enabling a critical business process. To become that de facto standard, you need to win at least half, and preferably a lot more, of the new orders in the segment over the next year. That is the sort of vendor performance that causes pragmatist customers to sit up and take notice. At the same time, you will still be taking orders from other segments.. So do the math.

Suppose you can get half of next year’s orders from the target segment—no mean feat considering that, prior to a couple of days ago, you hadn’t focused on it at all. Say your revenue target is $10 million over all. That means $5 million from the target segment. It also means that same $5 million has to represent at least half of the total orders from the segment if you are to have the desired market-leader impact. In other words, if you are going to be a $10- million company next year you do not want to attack a segment larger than $10 million. At the same time, it should be large enough to generate your $5 million. So the rule of thumb in crossing the chasm is simple: Pick on somebody your own size.

If you find the target segment is too big, subsegment it. But be careful here. You must respect word-of-mouth boundaries. The goal is to become a big fish in a small pond, not one flopping about trying to straddle a couple of mud puddles. The best sub-segmentation is based on special interest groups within the general community. These typically are very tightly networked and normally form because they have very special problems to solve. In the absence of such, geography can often be a safe subsegmentation variable, provided that it affects the way communities congregate.

The Target Market Selection Process

For selecting the target market segment that will serve as the point of entry for crossing the chasm into the mainstream market, the checklist is as follows:

- Develop a library of target-customer scenarios. Draw from anyone in the company who would like to submit scenarios, but go out of your way to elicit input from people in customer-facing jobs. Keep adding to it until new additions are no more than minor variations on existing scenarios.

- Appoint a subcommittee to make the target market selection. Keep it as small as possible but include on it anyone who could veto the outcome.

- Number and publish the scenarios in typed form, one page per scenario. Accompanying the bundle, provide a spreadsheet with the rating factors assigned to columns and the scenarios assigned to rows. Break the rating factors into two subtotals, showstoppers first, then nice-to-haves.

- Have each member of the subcommittee privately rate each scenario on the show-stopper factors. Roll up individual ratings into a group rating. During this process discuss any major disagreements about scores. This typically surfaces different points of view on the same scenario and is critical not just to getting the opportunity correctly in focus but also in laying the groundwork for a future consensus that will stick.

- Rank order the results and set aside scenarios which do not pass the first cut. This is typically about two thirds of the submissions.

- In a 400 degree oven, bake.. . (Oops! Wrong book. Sorry.) Repeat the private rating and public ranking process on the remaining scenarios with the remaining selection factors. Winnow the scenario population down to, at most, a favored few.

- Depending on outcome, proceed as follows:

- Group agrees on beachhead segment. Go forward on that basis.

- Group cannot decide among a final few. Give the assignment to one person to build a bowling pin model of market development, incorporating as many of the final few as is reasonable, and calling out a head pin. Attack the head pin.

- No scenario survived. This does happen. In that case, do not attempt to cross the chasm. Also, do not try to grow. Continue to take earlymarket projects, keep burn rate as low as possible, and continue search for a viable beachhead.

The 4 Fundamental Stages of the Technology Adoption Life Cycle

There are four fundamental stages in this process, corresponding to the four primary psychographic types, as follows:

1. Name it and frame it. Potential customers cannot buy what they cannot name, nor can they seek out the product unless they know what category to look under. This is the minimum amount of positioning needed to make the product easy to buy for a technology enthusiast.

Discontinuous innovations are often difficult to name and frame. The largely ineffectual category middleware is an attempt to name and frame a new class of systems software that lives between established platforms of enabling technology—the operating system, the database, and the network operating system—and established applications—say, financials, human resources, or sales force automation. It turns out that businesses are wanting to make all these applications interoperate, and to do that requires messaging software, transaction processing software, object brokering software, and the like. It is all very complicated technically and gives rise to sectarian fanaticism which nobody wants to deal with, so as an industry we have collectively agreed to throw it all in a bucket called middleware, and hope we can just keep a lid on it. The problem with all this is that we cannot keep it in the bucket. The need for it keeps calling it out. But once it gets out, because we cannot name it and frame it properly, all companies who provide it are stuck with a nasty marketing problem. Customers go into prolonged review cycles, religious wars break out, and sales get postponed as each situation battles over the same tired ground.

2. Who for and what for. Customers will not buy something until they know who is going to use it and for what purpose. This is the minimum extension to positioning needed to make the product easy to buy for the visionary.

As it becomes clear who can most benefit from these technologies to achieve a major strategic advantage, then they will have secured the necessary positions to develop their respective early markets.

3. Competition and differentiation. Customers cannot know what to expect or what to pay for a product until they can place it in some sort of comparative context. This is the minimum extension to positioning needed to make a product easy to buy for a programatist. Examples of this category have filled the preceding pages of this chapter. The key is to provide the reassurance of a competitive set, and of a market-leading choice within that set.

4. Financials and Futures. Customers cannot be completely secure in buying a product until they know it comes from a vendor with staying power who will continue to invest in this product category. This is the final extension of positioning needed to make a product easy to buy for a conservative.

The purpose of positioning is to put in place these sets of perceptions with the appropriate target customers in the appropriate sequence and at the appropriate time in the development of a product’s market.